Notes on the Program…

Good evening. “Chamber Music Treasures II ” is the next installment to a celebration of chamber music by composers of African and African American descent–who are now also identified by the anagram “BIPOC”. The inaugural program of two years ago is best described in hindsight as “the result of fortunate coincidences, patience and good timing”. In the past 24 months of hindsight however, these coincidences could not have been more felicitously understated!! The MLK national holiday of 2020 passed with scant mention to news of a “COVID-19” virus discovered in Wuhan, China. Barely six weeks after that performance, we would unanimously state that “the rest–AND the present--is indeed history!!”

The faculty artists of NCCMI paid Dr. King deferred tribute last year via an online presentation of the 2020 program with commentary and conversation between Waltye Rasulala and Dr. Timothy Holley interspersed and grafted between selections. It streamed online in late February 2021–a late but still fortuitous offering of the inaugural program during the final week of Black History Month. It seems equally surrealistic that the streamed “re-offering” of the first performance aired eight weeks after the attack on the U. S. Capitol Building. Months later–amid pandemic, growing calls and protests for social justice nationwide took hold following the deaths of Breanna Taylor and George Floyd in Louisville, Kentucky and Minneapolis, Minnesota at the hands of white police officers and the law enforcement community at-large. Citizens took to the streets nationwide calling for the defunding of police departments and protesting enforced lockdowns while the virus spread. Intensive care units were filled beyond capacity…and people died in record numbers daily. The relevance and potency of the “Black Lives Matter” movement at mid-year was matched only by the controversial tone and force of the landmark “1619 Project” bravely anchored by New York Times investigative journalist Nikole Hannah-Jones. The entertainment and fine arts communities, already in complete lockdown–also created ways to respond (“virtually”!!) and join the global calls for justice, equity and inclusion while awaiting the development, approval and distribution of the first available coronavirus vaccines nationwide for those in greatest need.

As we now comply with the third (and present) variant strain and responsive round of vaccinations, it is a pleasure to present this second program–hopefully live and indeed streaming as well!! The inaugural program featured the music of “le Chevalier” Joseph Boulogne de Saint-Georges, Adolphus Hailstork, Florence Price, Margaret Bonds, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and James Weldon Johnson. The 2022 program extends this tradition further, focusing on works of David N. Baker, Anthony M. Kelley, Florence Price, Chevalier de St. Georges, Adolphus Hailstork, Jessie Montgomery, George Walker, William Grant Still and James Weldon Johnson. This year’s program is also augmented by the welcomed presence of two guest ensembles, the United Strings of Color Quartet and the WCPE String Quartet, one of the laureate student ensembles of NCCMI.

The program opens with the first of three works of “elegiac” tone and expression. David Baker was the longest serving faculty member of the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University (1966-2013). In conjunction with Jamey Aebersold, Baker championed the institution of American jazz in education, pedagogy and publication. Originally a jazz trombonist, Baker switched to cello after an automobile accident ruined his embouchure. Although he was a prolific composer, his true calling was teaching: a list of his students taught by him and colleagues who commissioned works from him over the course of five decades easily read like American music living legend (which also includes Elizabeth Beilman!!). The Pastorale was composed in 1959, five years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the U. S. Supreme Court and the continued protests of the Civil Rights Movement. Baker would later incorporate it into the cantata “Black America” (1968), written in memory of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. This brief work has a carefree expression built upon an opening of major/minor scales and jazz harmonies, but a deceptive gesture at its quiet conclusion dispels that carefree disposition, leaving the listener to reflect upon it with tragic irony.

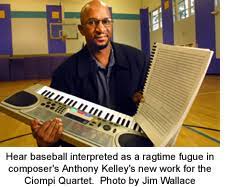

Anthony Kelley has kindly provided the following comment on “Sidelines”: “I have two older brothers; throughout our youth they were both impressively gifted in athletics. I looked up to them and their achievements, which included many impressive trophies. The string quartet, Sidelines, is a two-movement musical translation of aspects of sports that were most striking to my imagination as I watched from the bleachers. The second movement “Basketball” explores the joy and gracefulness of buoyancy, both in the game of basketball itself and the gravity-defying players on the court. (Incidentally, baseball is the “featured sideline” of the first movement.) Bouncy, elastic pizzicato notes accompany gliding bluesy melodic and harmonic events until they reach a gentle, conclusive phrase.” Sidelines was composed for the Ciompi Quartet of Duke University.

Florence Price’s output of Negro spirituals arrangements for voice and piano date from the full expanse of her years in Chicago, after having migrated from her hometown of Little Rock, Arkansas in 1927. Her arrangements (and those of many African American composers of that time) were modeled after the settings of Harry T. Burleigh (published by Ricordi in 1915), who sang spirituals for Antonin Dvorak during the Czech composer’s three-year American residency. By the 1920s the last surviving generation of former slaves were between 65-90 years of age; the experience of the African American former slave was still a living memory at that time. Florence Price met and heard spirituals sung by Malinda Carter, a former slave once owned by Squire Carter of Rutherford County, Tennessee. Malinda Carter’s granddaughter Fannie Carter Woods was a concert singer who sang several premieres of Price’s songs. “You Won’t Find A Man Like Jesus” is a meditative song of exultation that clearly speaks of the reflected experience of the Samaritan woman at the well in one of many Gospel accounts of documented encounters with “the carpenter’s son from Nazareth”. Its accompaniment recalls a smoothed-over syncopation often found in ragtime music. “Go Down Moses” (or “O Let My People Go”), one of the best-known examples within the African American folksong tradition, contains the easy makings of a major research effort in the mere estimation of its historical origins. It had to have been a functional protest and popular song during the years of American abolitionism, but exact historical placement of its “origin” is very difficult to determine in either place or time. The song first appeared in print as “The Song of The Contrabands” in 1862 in an arrangement by Thomas Baker based on the song heard by Lewis Lockwood, Chaplain at Union Fortress Monroe (near Hampton, VA). It was sung by the “contrabands” (slaves who defected to Union Army forces in Confederate states during the Civil War) for at least a decade before the broadside publication; Harriet Tubman knew of such “songs of protest” and used them in her work on the Underground Railroad a full decade before. When the Fisk Jubilee Singers sang the song on their tours of the British Isles and Europe, their version of the song was published by the American Missionary Association in 1872. By then the song was sufficiently well-known “across the pond” through the antislavery lectures Frederick Douglass gave on tour in Great Britain, Scotland and Ireland in 1846-1847.

The 2020 recital opened with a string quartet of Joseph Boulogne, le Chevalier de St. Georges. To date, the Quatuor pour le clavecin, violon, viola et basse is the only extant work written for keyboard and strings. The date of its composition is unknown, but it shares the same two-movement structure featured in the first published set of string quartets (Opus 1, 1773). A second detail of interest beyond the instrumentation is Saint-George’s membership in the Loge et Société Olympique, a Masonic order and chamber music society in Paris. He was inducted in 1771 and remained an active member for the rest of his life. The unique keyboard and strings instrumentation reflects a lodge requirement that stipulated lodge members compose a work for their instrument and the other lodge brethren. Just as Saint-Georges had composed some of the first string quartets in France around this time, this piano quartet may have also been first of its kind as well. ‘Le clavecin’ plays the lead musical role but also engages in limited dialogue with the strings; the cello is somewhat “liberated”--from merely doubling the left hand of the keyboard throughout!! The terse g minor first movement features melodic gestures that show a clear exchange of influence with the Mannheim School of Johann Stamitz. The second movement tonality is a lighthearted rondeau--“balanced” with both major and minor modes between song and dance!!

The reader’s indulgence is begged in the sharing of the next program note which is recycled from my doctoral dissertation recitals: “Adolphus Hailstork composed his Elegy for cello and piano in 1980; after having performed the Trio for Violin, Cello and Piano (1985) some years ago, he sent me a tape recording of a performance in which I had participated, along with a score and part to this work with the following note enclosed: “Dear Tim, I don’t recall ever having sent you this short simple ELEGY. Perhaps you can use it. Best wishes, Adolphus. P.S.—If you ever do it, how about sending me a tape?” This “short, simple” piece has a quiet intensity within it that is often associated with grief and bereavement. It is also a somewhat anomalous example of an “African-American elegy”, in light of the occasionally plaintive tone of the Negro spirituals. Its withdrawn atmosphere is so removed from the highly emotional norm of expression at a time of grief and sorrow. The expressive center of the Elegy is the private and noble outpouring of grief as opposed to the expectant visible response of “outburst” (e.g., Moneta Sleet Jr.’s moving photograph of Coretta Scott King holding her youngest daughter Bernice at the funeral of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968). Direct references are made to the blues in this work in terms of both vocal and stylistic inflection. Although the better-known Elegie, Opus 24 of Gabriel Faure chooses a contrastively extroverted manner of musical expression, Hailstork instead favors an austere and introverted approach, giving the cello a melodic line that is much more withdrawn and even “ascetic” in disposition. Although the piano has the larger instrumental role, it is the cello that has the task of extracting a wealth of deeply profound expression from a single melodic line (or even a single pitch). Thematic connections to Beethoven (Sonata for Piano, Op.81a, Les adieux) and Gustav Mahler (Symphony No.9, Mvt. I) can be found in the blues-affected “Farewell” melody stated by the cello. The influence of the blues in the “farewell” melody--only becomes apparent as the harmonic contour of the work takes shape. The Elegy was composed for the cellist James Herbison (1947-2008), a colleague of the composer at Norfolk State University.

Jessie Montgomery provides the following about the creative and developmental history of her work, Strum: “Strum is the culminating result of several versions of a string quintet I wrote in 2006. It was originally written for the Providence String Quartet and guests of Community MusicWorks Players, then arranged for string quartet in 2008 with several small revisions. In 2012 the piece underwent its final revisions with a rewrite of both the introduction and the ending for the Catalyst Quartet in a performance celebrating the 15th Annual Sphinx Competition. Originally conceived for the formation of a cello quintet, the voicing is often spread wide over the ensemble, giving the music an expansive quality of sound. Within Strum I utilized texture motives, layers of rhythmic or harmonic ostinati that string together to form a bed of sound for melodies to weave in and out. The strumming pizzicato serves as a texture motive and the primary driving rhythmic underpinning of the piece. Drawing on American folk idioms and the spirit of dance and movement, the piece has a kind of narrative that begins with fleeting nostalgia and transforms into ecstatic celebration”.

In his fourscore and sixteen years George Walker lived four “musical lives”: concert pianist, chamber musician, composer and professor. He belongs to a unique group of African-American composers and performers who had career “trajectories” distinguished by their prodigious beginnings, their conservatory training and concert performance, including Florence Price, Robert Nathaniel Dett and Margaret Bonds. Like his earlier contemporaries, he had to maintain a “second career option” after conservatory study and his New York recital debut– because of limited performance opportunities accessible to him on account of skin color and the larger concert world’s slowness to change its “flexibility of marketable image”. The common phrase still uttered (a bit less openly) today “the world just isn’t ready yet for a black concert pianist or symphony orchestra conductor” preceded his generation and still mirrors the challenges of equal regard beyond skin color that we face today. Yet George Walker still established himself as both a virtuoso pianist and composer of equal stature, composing solo piano music, chamber music, vocal, choral and orchestral music. It goes without saying that he was blessed with apparent genetic longevity: his sister Frances Walker Slocum (1924-2018) also lived well into her nineties and enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a concert pianist and professor of music at Oberlin College. George was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Music (at age 74) for his composition “Lilacs” for soprano and orchestra in 1996, a tribute to the tenor Roland Hayes. One of his first serious works he named Lament for Strings (also the middle movement of Walker’s First String Quartet, an early work composed during his graduate study at Curtis, published in 1946). Walker revised and renamed it Lyric for Strings in 1990, upon which it became one his most-performed concert works. It has a shared “kindred spirit and influence” with the Adagio for Strings by Samuel Barber, as both men studied with Rosario Scalero at the Curtis Institute of Music. The Lyric for Strings is dedicated to the memory of Mrs. Malvina King, George’s grandmother (a former slave who passed away shortly before the completion of the string quartet). It was also performed in July 2021 at a vigil for violinist Elijah McClain on the steps of the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

William Grant Still was one of the most important African American composers of the 20th century. He is nicknamed “the dean of Afro-American composers" on the strength of a quote (made in 1945) by Leopold Stokowski: “Still is one of our greatest living composers”. A similar statement of critical acclaim followed a decade later from a Belgian music critic: “This American composer shows remarkable qualities which place him as one of the very greatest living composers of the New World: a sense of immediate observation; the taste for a rigorous and brilliant orchestration; spontaneity and sincerity characterize his compositions”. His music was also championed by composer and conductor Howard Hanson, who conducted the premiere of Still’s “Afro-American” Symphony in 1931. The Danzas de Panama dates from 1948, based on a collection of Panamanian folk tunes which were collected by the American violinist, actress and ethnomusicologist Elizabeth Waldo in the 1920’s. (At last web check, Ms. Waldo is still living on the West Coast…at the youthful age of 103!!) Of the suite’s four dances, each has at least two and sometimes three separate dances within it. The last movement, Cumbia y Congo begins with a percussive hand-pounding to a high-spirited and fast dance. The choreographic tradition of the Panamanian Cumbia is this: couples advance to the center of the room, both men and women, and gradually form a circle of couples. The dance step of the man was a kind of leap backwards as the woman slid forward carrying a lighted candle in her hand holding a colored handkerchief. Notes provided in the score to this movement also refer to ladies holding a candle during the dance, perhaps recalling the holiday tradition of parading at night carrying a flambeau, not a candle (cf. the French Christmas carol “Bring A Torch, Jeannette, Isabella”). A true match for the dance, the rhythm aspect of this movement sounds purely African in origin but receives an immediate and heavy dose of Latin melody added to the mix. A brilliant, exciting Coda (“tail”) section brings the work to a rousing close, an impressive tour de force. In the spirit of community and communal song, this program closes with “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing” of James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond Johnson. James Weldon Johnson penned the poem in 1900 for recitation by Johnson’s students at segregated Edwin M. Stanton Preparatory School in Jacksonville, Florida in observance of President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Booker T. Washington was the honored guest at the premiere recitation. John Rosamond Johnson set the poem to music in 1905, and the NAACP adopted and dubbed it “the Negro National Anthem” (despite the turbulence of the “Red Summer of 1919”) for its hopeful insistence and deep faith expressed in its three verses. We sing and play this anthem, both to close the program and open a new year of musical heraldry!! TWH

Song Texts:

You Won’t Find a Man Like Jesus (arr. Florence Price)

“Like Jesus, no you won’t find a man like Jesus. You may search from sea to sea, but this thing is clear to me, that you won’t find a man like Jesus. You can search up in the air, but you won't find him there.”

Go Down, Moses (arr. Florence Price) “Go down, Moses, ‘way down in Egypt land. Tell ol’ Pharaoh to let my people go.!” When Israel was in Egypt’s land, “Let my people go!” Oppressed so hard they could not stand “Let my people go!” This spoke the Lord, bold Moses said. “Let my people go!” If not I’ll smite your first-born dead. “Let my people go!” “Go down Moses, way down in Egypt's land Tell ol’ Pharaoh to let my people go O let my people go!”

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing (James Weldon Johnson)

“Lift every voice and sing, ’Til earth and heaven ring, Ring with the harmonies of Liberty; Let our rejoicing rise High as the listening skies, Let it resound loud as the rolling sea. Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us, Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us; Facing the rising sun of our new day begun, Let us march on ’til victory is won. Stony the road we trod, Bitter the chastening rod, Felt in the days when hope unborn had died; Yet with a steady beat, Have not our weary feet Come to the place for which our fathers died. We have come over a way that with tears has been watered, We have come, treading our path through the blood of the slaughtered, Out from the gloomy past, ’Til now we stand at last Where the white gleam of our bright star is cast. God of our weary years, God of our silent tears, Thou who has brought us thus far on the way; Thou who has by Thy might Led us into the light, Keep us forever in the path, we pray. Lest our feet stray from the places, our God, where we met Thee, Lest our hearts drunk with the wine of the world, we forget Thee; Shadowed beneath Thy hand, May we forever stand, True to our God, True to our native land.”